When “Vu” was launched in Paris at the end of March 1928 as a novel and stylish magazine, few expected the. Rippling effect it was going to have on photography, design and the world of publication at large.

Its founder, Lucien Vogel, left the feminine press where he started his career, to launch Vu (as in “seen”). His clear engagement with pacifism and his horror of the damages of the. Great War propelled the writing and to some extent the initial photography, although the reading public was. Not of the militant sort. The political principles of the magazine were a clear mirror of the troubled period that. France was undergoing, in which weak governments were falling one after the other.

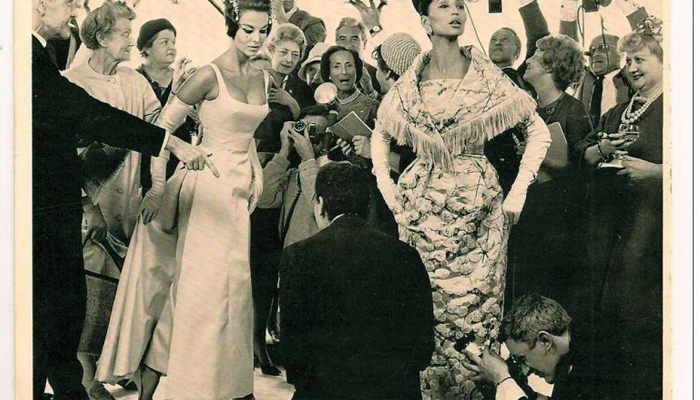

And yet, the mystique created around Vu stems from the crossroads where the world of new printing. Process and photography found themselves. Like today’s internet, new technologies set in motion creativity and inspiration. A new world opened up where. Graphic designers and photographers were experimenting with photomontage and typography. The trailblazing photos of the likes of. Man Ray, Brassaï, Cartier-Bresson and Gaston Paris filled the pages of this weekly, engaging in an experiment where the rules of content and image were being written. With each issue. In 1932, the famed Alexander Liberman, later of Vogue, was appointed artistic director.

The downfall of Vu, which stopped printing in 1940, was curiously brought about by the defiant positioning of. Vogel as a staunch defender of the Spanish. Civil War republicans. Having given up his pacifism and witnessing the menacing advance of. Hitler, he adopted what was considered by many a political attitude too far to the left. The shareholders of the magazine decided to fire him. Thus ended one of the most audacious and. Avant-garde experiments in the world of publication. It was a harbinger of what lay ahead for France.